Experimental breakthrough by Pacific Fusion clears major obstacle to affordable commercial fusion

An electric pulse of 22 million amps in one-millionth of an eye-blink shows success of radically simpler design for pulser-driven inertial fusion.

Pacific Fusion achieved a major breakthrough in fusion energy research by showing how to achieve pulser-driven inertial confinement fusion (ICF) with a radically simpler design, removing a significant roadblock to practical fusion power at scale.

ICF uses pulses of either laser light or electric current to implode small ‘targets’ containing fusion fuel, causing them to release massive amounts of energy on each ‘shot’. It’s the only approach ever to achieve controlled fusion ignition on Earth, first demonstrated at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in 2022.

With experimental proof of the scientific conditions that produce ignition, NIF’s ICF achievement has now shifted the focus from whether fusion can work to how to make it practical and affordable. In both the laser and (electric) pulser-driven approaches, critical components—the fusion target and nearby hardware—are destroyed on each shot and would need to be replaced, roughly every second in commercial power plants. From an economic standpoint, that’s a showstopper, because the cost of the components destroyed far exceeds the value of the energy that would be released on each shot.

For laser-driven ICF systems, the targets are expensive. Pulser-driven ICF has a potentially lower-cost, more robust, and more modular path, because electric pulsers are less costly than lasers and use much simpler targets. But the approach requires “pre-magnetizing” the fusion fuel in the instant before a large electric pulse is triggered to drive fusion. In the traditional design, called “MagLIF,” this has been done by surrounding the targets with large magnetic coils that are destroyed on each shot.

To unlock low-cost pulser-driven fusion, scientists have needed a simple, inexpensive way to pre-magnetize the fuel without external magnetic coils.

That’s what Pacific Fusion, in partnership with our collaborators at Sandia, has now accomplished. See more in our press release.

Above: Members of the Pacific Fusion team at Sandia National Labs

We successfully demonstrated a new family of target concepts — designed by Pacific Fusion and tested on Sandia’s powerful Z-machine — that is inexpensive and eliminates the need for external magnetic coils. Instead, the simple targets, made of plastic and aluminum, create their own internal magnetic field to pre-magnetize the fusion fuel. Pre-magnetization is desirable for pulser-driven inertial fusion energy because it helps trap heat in the fusion fuel, letting it ignite more easily.

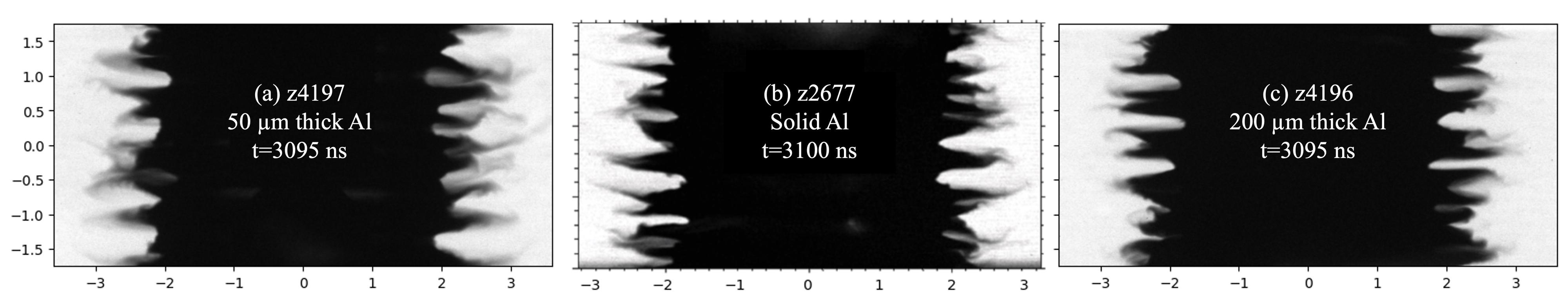

Above: Pacific Fusion experiment results, conducted on Sandia’s Z-Machine; image shows X-ray radiographs from the present experiments with thin (a) and thick (c) aluminum layers showing no significant differences in instability amplitude or spectrum compared to previous solid aluminum experiments (b), demonstrating that simplified composite liners perform equivalently to solid metal liners. Image (b) from: Awe et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 065001 (2016)

Pacific Fusion won a competitive selection process to gain access to four shots on the Z Machine in Albuquerque, the world’s most powerful pulsed-power facility.

In October, we traveled to New Mexico, bringing with us two versions of a new target design, developed with Pacific Fusion’s recently validated modeling and simulation software suite, to eliminate the need for copper coils to pre-magnetize the target.

The targets are small metal cylinders, about the size of a pencil eraser, composed of a layer of conducting aluminum bonded to an insulating plastic. (The thickness of the aluminum was 50 microns in one version, 200 microns in the other — roughly a human hair vs. a sheet of paper.)

With our Sandia collaborators, we took four shots over five days. Each sent 22 million amps of electric current through a target in just 120 nanoseconds, a million times faster than the blink of an eye.

Tiny magnetic sensors placed in each target, called B-dot probes, measured the penetration of the magnetic field into the target.

The experiments showed that, with these materials alone, the design enabled magnetic fields created by the current to enter the target — eliminating the need to pre-magnetize it.

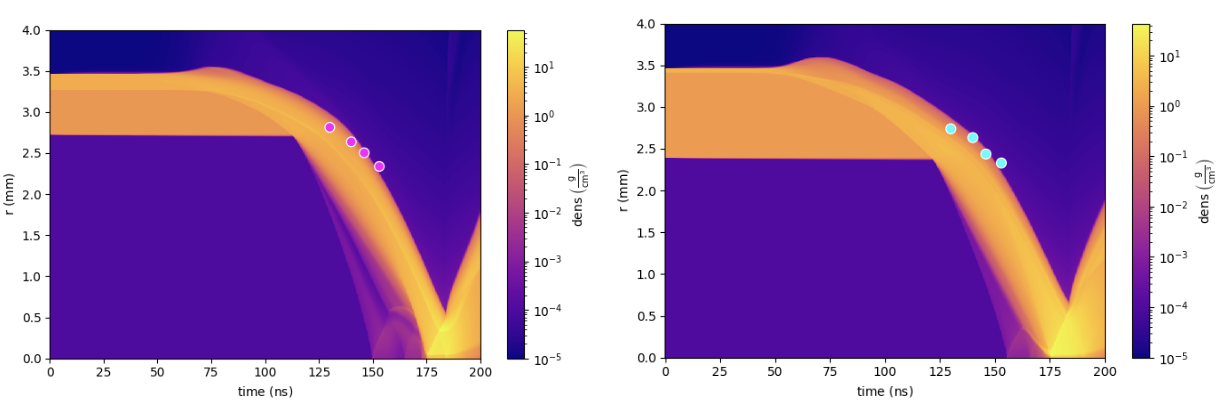

We found that the thickness of the target’s conducting layer affected how quickly the magnetic field moved inside the target. A thinner aluminum layer allowed the field to enter faster and more strongly, giving us a new way to fine-tune performance.

Critically, our simulation tools accurately predicted how targets behaved during this experiment. As we shared in September, we worked with the Flash Center at the University of Rochester to model pulser-driven inertial fusion reactions. However, we had not yet experimentally validated the code for target designs. The new experimental results give us confidence that FLASH can help us design future targets more efficiently and test new target materials. Next, we’ll explore different metallic conductors and insulating materials such as ceramics to further improve results.

Above: Experimental simulation results showing the evolution of the 50 µm thick (left) and 200 µm thick (right) aluminum composite liner targets compared to experimentally measured data points—indicating that simulations can be used as a tool to design high-gain fusion targets.

The results also suggest that we can further simplify the process of driving fusion. In the MagLIF experiments, the targets are not only pre-magnetized but also pre-heated with a laser. Even though the pre-heating laser is not destroyed on each shot, it’s an added complexity. In the next iteration of experiments, we will aim to show that we can eliminate the need for laser pre-heating in addition to pre-magnetization.

Showing that the target itself can now perform the functions that previously required external hardware dramatically simplifies the entire target-chamber architecture compared to traditional designs, enabling us to build a system that meets the criteria for enabling economically viable fusion power.

In September, we selected Albuquerque as the site of our Demonstration System, designed to achieve net facility gain — more fusion energy out than all the energy stored in the system — by 2030. By removing a key barrier to repeatable, affordable fusion shots, these developments keep us on track to deliver a first commercial fusion systemby the mid-2030s.

We’re grateful to the Z-Machine’s operations team for their collaboration and for showing how public-private partnerships in fusion can deliver breakthrough results.

Want to build with us? We are hiring.